Want to travel along?

— We cannot truly be peacemakers if we have not found peace within. —bell hooks

Owyhee Canyon

Welcome to our exploration of wonder. It’s 9:00 at night in Owyhee Canyon in far Eastern Oregon. The sound of crickets and nearby Succor Creek rushing over rocks have replaced the hum of traffic and neighbors from our home just outside Portland, Oregon. My husband, Dwayne, reclines in his new Nemo Stargaze outdoor chair also writing. Our dog, Neo, stretches out on his little blue outdoor bed. I sit at a picnic bench, writing my introduction. All three of us hiked for a few hours today and then drove into one of the most wondrous canyons I’ve ever seen.

Cow watching us hike

It rivals Cappadocia in Turkey, a place world-famous for sandstone cliffs shaped like fairy chimneys. Here, though the cliffs as beautifully sculpted and even more colorful, because they are in this remote land in hard-to-reach eastern Oregon, they are barely known. We are alone in the camp. Earlier three generations of men, a grandfather, son, and grandson, camped near us. They came here to find opal rocks. For a couple days there was also a lone camper, a man who sought to prove that a rare snake actually does live in Oregon. After the weekend, the generation of men packed and left, and then the next night our snake hunting neighbor left too. It is our first time alone since we’ve started this journey. It’s nice, peaceful. We are not sure when we are leaving. All that pulls us now is getting to Wyoming before it gets too cold.

Relaxing in the creek

We have only been traveling a couple months but the rhythm of this new life is starting to sink in. I recognize a buzzing tension that has been with me for so long I had been unable to see it before. Here amid the buzz of insects and frogs, I couldn’t help but notice my own nervous rhythm. I am slowly learning to let that go, releasing my stress the the fragrant desert air. And there is a part of me that isn’t sure how to be without this tension. Who am I without the constant pressure of work? I have some work. I am starting my coaching business and finishing up my mindful meditation program. But it’s not the same intense pace as teaching and coaching in a public school setting. I’m grateful for this break to clear my head and clarify my purpose. Here in Oyhee Canyon I wonder if I can find a way to keep this peace I’m starting to feel inside me when this is all over.

“I wonder if Americans are irreconcilably fractured. Is there a way to see us as a community, as interconnected? ”

I also have other questions I hope to answer this year. Questions I’ve been thinking about for a long time. One is the reason we chose to travel. I wonder if Americans are irreconcilably fractured. Is there a way to see us as a community, as interconnected? I’ve been frustrated for so long with this country and its politics, with White Supremest Culture, with income inequality, with vitriol and vilification coming from both the right and the left, with the incessant fear of school shootings. . . yet I know frustration and anger are at odds with what I believe as a Buddhist. In Buddhism, my reaction to these issues is called the second arrow. Sorrow and pain are inevitable, but the suffering we put ourselves through over the pain or threat of pain is optional. Lama Rod Owens, Buddhist author and activist asks a question that resonates with my own dissonance in his book Love and Rage: The Path of Liberation through Anger. “What would it look like,” Lama Rod asks, “if we formed our activist communities around joy, not the suffering or the anger, as a basis for our change work?” I want to believe that his question is not merely aspirational. In her book, Belonging: A Culture of Place, bell hooks addresses this dissonance. She writes that to “embrace community and we must accept those who are different, and this means that we must also find a way to positively connect with folks who express prejudicial feelings, even hatred. Committed to building community we are called by a covenant of love to extend fellowship even when we confront rejection. We are not called to make peace with abuse but we are called to be peacemakers.” Can I find a way to come to such peace in the land I live? That’s what I want to find out.

“ [to] embrace community and we must accept those who are different, and this means that we must also find a way to positively connect with folks who express prejudicial feelings, even hatred. Committed to building community we are called by a covenant of love to extend fellowship even when we confront rejection. We are not called to make peace with abuse but we are called to be peacemakers.”

So we are traveling the West. We have only a year, so we chose to narrow our scope to one area because traveling the entire country feels like a marathon where we would end up merely tagging states. We intend a slower exploration of both place and community. We want to fall in love with the US again, to find wonder. Where better than the West?

How can I talk of travel until I have told you from where I have traveled. The external places and some of the internal too. Some insight into the complexity of my own political lens before I delve into that of the US. The other complexities will come out in my prose, I’m sure. But this is harder to share, and so best get it out of the way now. Best to get your outrage out now of my beliefs, mistakes, and wavering allegiances. For one of my favorite quotations is from one of my favorite poets, Walt Whitman, who writes, “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitudes.”

Though I lived in Oregon for the last twenty-two years, working in the same school district, raised a daughter, blending families, I spent my first eighteen years in New Hampshire and that mark is indelible. The tagline on our license plates is “Live Free or Die.” Something I never thought twice about until my college friends in New Jersey teased me. The smell of libertarian may have been invisible to me, but not to the folks who are part of the Free State Project (FSP), a group working toward getting 20,000 libertarians to move to NH to create a community for libertarian ideas to flourish, or as the Boston Globe wrote, to “undo New Hampshire government from within.” About two thousand FSP members have made the move and, more importantly, inserted themselves into state and local politics. Why my state? In their website, they explain that they chose New Hampshire because of it’s low population, but I think they took one look at the plates on the back of our cars and thought that’s the place for me.

Why do I begin my biography by talking about this radical political wave moving into the state I was raised? To begin with, for good or bad, I’m a New Hampshire gal at heart and that rugged individualist spirit is my foundation and my shadow-self. Second, and perhaps even more importantly, I would bet you anything that few of my New Hampshire family knows anything about the FSP, and if they do, I suspect they’ve dismissed them as typical nut jobs. If you were to read the national newspapers, the FSP folks have shaken the entire state, but that just isn’t true to the lived experience of most New Hampshirites.

“ I hope that we are interconnected more than we realize. More than hope, I’m betting this year on it.”

I believe that political camps—which are growing angrier and more intransigent on both sides—are not the only way to look at our communities. Emotions are elevated for sure. I’ve even heard level-headed friends talk of an impending civil war. In the wonderful documentary featuring the Dalai Lama and Desmond Tutu, Mission: JOY Finding Happiness in Troubled Times, the Dalai Lama cautions against a singular news-fueled viewpoint. He says that “then [people will] feel more hopelessness. And feel all humanity [is] bad and our future [is] not much hope.” This is one of the reasons I’m on this journey. I am determined to understand this country from more than just the political lens. To do that I need to get past my own introverted awkwardness and quick judgements. I want to talk to people, to see them in all their complexity, and to connect. I hope that we are interconnected more than we realize. More than hope, I’m betting this year on it.

My desire to find connection has been amplified by my studies In Buddhism. I aspire to live into Buddhist beliefs, and in particular the belief that each of us belongs to the other. You can already see my dilemma. Interconnection is a tall order for a person raised on rugged individualism, but I’m determined to try. I believe our cultural sanity depends on this.

For you to understand how I’ve gotten to this place, let me give you a few details. Here is a brief account—more like skipping stones on a lake than an actual immersion in water.

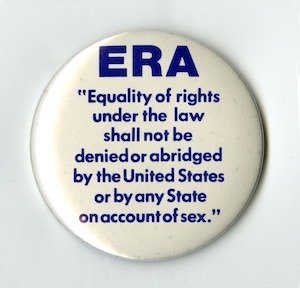

I wore this button in middle school

In middle school I wore political buttons, my most prized button was pro-ERA. For those of you too young to understand, ERA stands for the Equal Rights Amendment, which would have granted equal rights to women. You may not know anything about it because though it passed in 1972, it didn’t get ratified in 1979. I still remember the rhetoric. The opposition had coupled ERA with women getting drafted into war. This was just after the Vietnam war, and so that fear was real. I think many women who at heart believed in the spirit of the Amendment voted against it or abstained because of a deep fear of getting drafted. This was my first clear recognition of the power fear had to stop change in its tracks. To this day women are still not earning the same wages as men, are still fighting for equality. I don’t know if that amendment getting ratified would have changed anything, but to my middle school mind, this loss was inconceivably devastating. What I heard was that my country did not care about women, and I believe I internalized that for many years. Maybe I still do.

“ I remember that I didn’t get much of an applause and I also remember that mandatory seatbelts DID pass at Girls State though not in the actual state of NH where you can still drive without a seatbelt today. ”

In high school I was chosen to be one of the Girls State representatives from our small town. If you aren’t familiar with Girls State and Boys State, they are cool opportunities sponsored by the American Legion. While in high school, students get to occupy the state capital and vote on real issues as if they are actually a state representative. One of the issues we debated on the floor was whether or not the state should mandate the wearing of seatbelts. When my hand was chosen, I leaped to my feet, and gave an overly passionate speech on how we should vote against this mandate. I think my main point was that no one should choose for us—you know, Live Free or Die. I remember that I didn’t get much of an applause and I also remember that mandatory seatbelts DID pass at Girls State though not in the actual state of NH where you can still drive without a seatbelt today. That’s right, every other state and the District of Columbia require seatbelts, except New Hampshire. I should confess that even as I was passionately arguing against the seatbelt law, I always wore one and always will. But my choice, right?

“Watch an episode of Gilmore Girls to see a New England style town hall vote in action. ”

My senior year of high school, I won a thousand dollar scholarship for my patriotism. You may know that the New England town halls are a form of direct democracy. This means that community members who attend the meetings actually legislate policy and budgets through their votes. This is very different than most other places where town hall meetings are held by politicians only to listen to constitutes and do not give them the power to legislate. Watch an episode of Gilmore Girls to see a New England style town hall vote in action. The Free State folks have taken advantage of this system. In Croydin, NH, a FSP member voted to slash the town’s education budget in half, basically rendering the schools inoperable. Sometimes even in direct democracy there is apathy, and on that day there were so few people at the town hall meeting the FSP member, with the help of his wife on the school board, was able to get his votes. Shocked, the townspeople mobilized, and 379 people showed up at the next meeting, enough to overturn the last vote. A close call for sure, and my guess is that there will be more. Back to my own story, in my senior year of high school, my town gave out thousand dollar scholarships to a few of the best essays. I can’t remember the actual prompt but it had something to do with democracy or citizenship. I still remember my first line, “Thomas Jefferson once wrote that ‘all men are created equal’ and it is this foundation that makes the United States great.” Naturally, with a line like that I was one of the winners. Also I had learned how to temper my speaking after the Girls State fiasco.

Drew University

At Drew University, a small liberal arts college in New Jersey, I learned to march. This was the 80’s so there wasn’t a lot of action but I found it: protest for our university to divest from South Africa until Apartheid ended, a pro-choice march in Washington, DC. I’ve always enjoyed a good march, the solidarity, the excitement, the feeling of something larger than myself. In college, I studied history and English Literature and focused on the impact of colonialism, on feminist literature, and on counterculture of the sixties. I started to see the negative impact of US policies in this country and the world, and I was especially conscious of the absurd power of the US military machine. What rose in me was a conflict between an urge to make the world better, and an immobilizing dread.

Me in a Buddhist Monastery in Pokhara, Nepal

After college, still uncertain what I wanted to do, I joined the Peace Corps where I lived in a Nepali village where people had been subsistence farming since time immemorial. Nepal exists because China and India find it convenient to have this little land the size of North Carolina between them. Nepalis understand their vulnerability, and yet they dance, laugh, sing, gossip, and work harder than anyone I’ve ever seen. While living there, the US went to war with Iraq and I was completely flummoxed that the US couldn’t see that going into Iraq was a bid for oil. I had by now seen a lot more of the world and I would call my political lens that of world citizenship. Blind nationalism of any country seemed to me then, and now, small-minded.

“Blind nationalism of any country seemed to me then, and now, small-minded. ”

If I were skipping rocks, this last jump would take the rock clear out of the pond, but I want to skip the travel through my life all the way to 2016. When Trump became president, I lost my mind. So did my dad, but for very different reasons. My father and I often buttered heads, but until Trump, our debates had been rooted in mutual respect. I’m sorry to say that these were some of our most volatile arguments. I also realize with the clarity of hindsight that our arguments were bigger than Trump. What my dad could not say to me was “your mother is sinking into dementia and I don’t know how to handle it.” Instead he told me that he didn’t care about climate change because he wouldn’t be alive to see it’s affects. Trump’s anger resonated with my father because, frankly, my dad was angry. I didn’t help any. Rather than say, “Dad, I get it. Mom’s decline is scary and I’m here for you.” I went at him about Trump’s language, brought articles, showed graphs. He only dug in deeper and bought a Trump t-shirt. My anger shocked us both. His anger shocked up both.

“It was easier to be angry at something out there than to face the pain of what was happening right before our eyes.”

Finally, we agreed to disagree. And in the space that provided, I saw that not only was my mom impacted by dementia, but my dad had the beginning signs of Alzheimers. No wonder he was so angry! For both of us, it was easier to be angry at something out there than to face the pain of what was happening right before our eyes: the decline of Richard and Anne Tkaczyk.

“we don’t set out to save the world. we set out to wonder how other people are doing and to reflect how out actions affect other people’s hearts.”

Eight years later both of my parents have passed away. My dad passed in February from cancer, and my mom passed away of a broken heart, three months later to the day of the my dad. My greatest regret is that I fought with my dad over a man who had no real connection to our actual lives. The loss of my dad, and my regret over our fights, has soured me on the political lens, or at least a political lens sharp with anger. Buddhist nun and author, Pema Chödrön writes, “we don’t set out to save the world. we set out to wonder how other people are doing and to reflect how out actions affect other people’s hearts.” I’m going to try and be open enough to this kind of wondering. I am determined to to find a new path forward. I believe my sanity depends on this.

This last October I flew to New Hampshire to help care for my dad for a month. While I was there, my husband and I had long talks on the phone. It was during one of those long talks that we hatched this plan to travel the West for a year. My husband’s father had passed just a few weeks prior to me heading out to care for my dad. Both of our dads had a similar story. They worked hard and talked wistfully about retirement for years. But both were unable to fulfill their dreams. Dwayne’s father had a stroke and my dad dealt first with my mom’s cognitive decline and then with his own.

After caring for my dad, I returned home and Dwayne and I sat down our three grown kids and told them our plan. Then we talked to a realtor, prepared our house for sale, and began researching full-time living and trailers. We bought our trailer, Ayla, and then a truck to pull her. My dad passed. Our house sold. We were living at an RV park just below Portland until I finished out my teaching contract when my mom passed. And then right after school finished, we pulled Ayla out of her parking spot and started our travels.

“Want to travel along?”

In some ways I feel like Forrest Gump running aimlessly back and forth across the country after he lost Jenny. In other ways, traveling feels more real, more “right” than anything I’ve done in a long time. Either way we are committed to a year to follow wonder as we travel the West. Want to travel along?

W for chasing Wonder